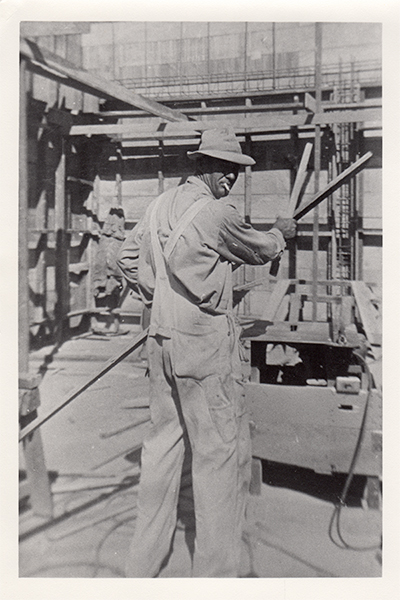

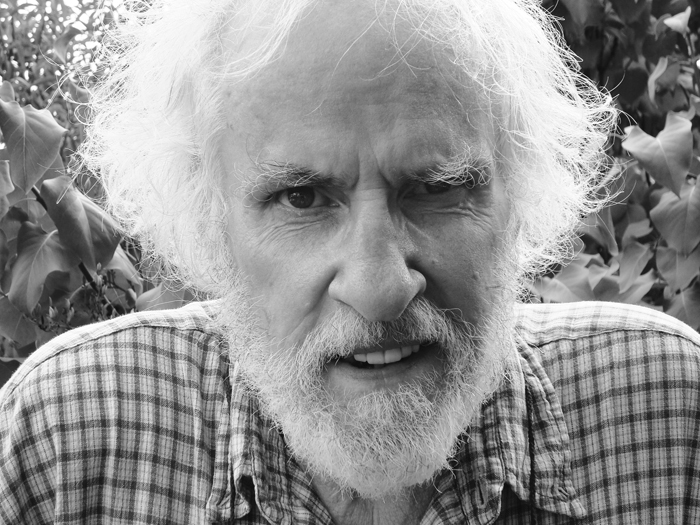

Young David Bearden being a Cowboy

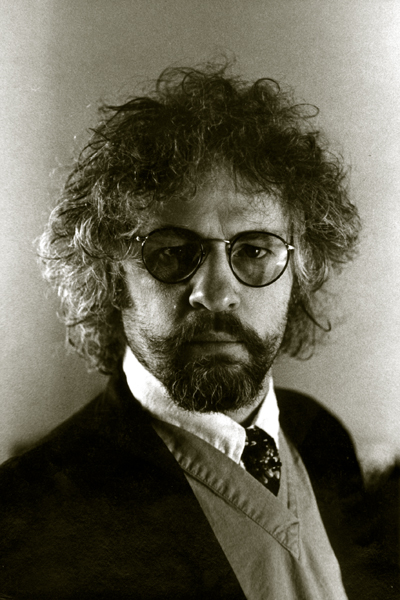

Michigan Avenue, Blythe, CA

Early Life and Adolescence (1940-1958)

David Bearden is the surviving brother of twins born in the desert town of Blythe, California located in the Palo Verde Valley, a narrow verdant strip of cultivated land on the west bank of the Lower Colorado River. Blythe in 1940 was populated by a mix of tough people, many of whom were refugees who had arrived there during the Great Depression, and lived in relative isolation in the northwest sub-region of the blistering Sonoran Desert. Successive waves of immigrants and settlers eventually led to a demographic breakdown for Blythe that was said to be one-third Anglo, one-third Mexican and African-American, and one-third Okie. (Okie being a derogatory term for the rural migrants to California from the Southwest and Great Plains states in the 1930’s who had been displaced by the effects of environmental upheaval and the Great Depression.)

Having fled the Dust Bowl regions of Texas and Oklahoma, Bearden’s parents, Omer Adair Bearden and Nellie Corene Bearden, were a part of the Depression-era exodus. After arriving in Blythe, they moved into a converted Pullman railroad car with an addition built by the father and raised their family of two girls and three boys. There were a few acres with a small vegetable farm, two cows, a rental unit, and laundry house. Omer Bearden worked as a carpenter and contractor, and Nellie took care of the home while cultivating a love of music and developing her skills as a seamstress. The family was of Irish ancestry and followed the Southern Baptist faith. David Bearden lost his twin brother, Danny, at the age of two, when the young boy fell out of the family car at highway speed while traveling between California and Oklahoma. Danny suffered multiple injuries and passed away almost a year later on December 22, 1942, from complications resulting from the accident.

As a boy, Bearden liked to entertain by reciting lyrical poems and telling stories. He also enjoyed singing songs for church, fraternal organizations, and on the KYOR radio station in Blythe. However, by his adolescence, he started getting into trouble. Life was hard in the hot 120-degree poverty-stricken town of arrow-weeds, alkali flats, and cracked sidewalks. At 12, he and some other boys sank a D-7 Caterpillar bulldozer into a canal. Then at age 14, he and a local kid named Joe Wells stole a car and drove it 200 miles to Eloy, Arizona, before they got busted. For these and other actions, he was sentenced to Riverside County Juvenile Hall, where he did some time. He was subsequently required to enroll at the Elsinore Naval and Military Academy, where he began writing his poetry.

Not permitted to return to Blythe, Bearden moved in with his older sister Dortha and her family in Mangum, Oklahoma to attend high school during his junior year. Initially, the transition was not easy for him, being a California native. He was ostracized and disliked by many of his Oklahoma peers. It wasn't long until he reverted to his defiant ways and moved out of his sister’s home. He struggled through school, living alone and working for a family named Avery, who ran the Blue Moon Café on the courthouse square. One of his duties was to take the kitchen swill and feed it to the hogs on the family’s farm. Despite his hardships, he excelled in his studies, especially in English, and became co-captain of the football team during his senior year. He proudly soloed the song “You’ll Never Walk Alone” at his graduation ceremony in 1958 and was showered with gifts by his teachers and various citizens of Mangum, who now wished him well. David Bearden had gone from being just another 50’s juvenile delinquent in California to Mangum’s “Golden Boy.”

University of Tulsa (1958-1962)

Bearden enrolled at the University of Tulsa with a scholarship in the summer of 1958 and majored in English Literature. He was never seriously engaged in the program. His participation involved occasionally making it to class while attending every off-campus bohemian social function he could find.

During an English class, he met his future wife, Judith Brownfield, who had a young daughter. The two of them enjoyed discussing the works of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy as their relationship developed. Bearden possessed a love for words, the more obscure and precisely descriptive, the better, and enjoyed sending people to the dictionary. He had a passion for all types of literature. At this point, his literary heroes were Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Dylan Thomas, and Kenneth Patchen. He introduced Judith to The Catcher in the Rye and other works by J.D. Salinger, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and The Subterraneans, as well as the novels of Vladimir Nabokov.

Bearden also became acquainted with other TU students who shared similar interests in literature and poetry, including poets Martin Cochran, Richard White, and upper-classman Ted Berrigan. Ted likewise found David to be especially stimulating and turned him on to the idea of becoming a writer. By this time, they both had discovered the writings of the “Beats” such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, and began publishing their own poems in the campus literary magazine, Nimrod. They also contributed poems to The White Dove Review, the avant-garde literary journal that local high school students Ron Padgett, Joe Brainard, Michael Marsh, and Dick Gallup jointly produced. Some of Bearden’s earliest work appeared alongside that of well-known writers such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Paul Blackburn, Judson Crews, Peter Orlovsky, and Clarence Major.

He was simultaneously becoming an accomplished, self-taught guitar player. He had a natural ear and could pick out a tune and play it after hearing it only a few times. This was the era of the folk music revival when everyone was listening to the records of the Weavers, the Carter Family, Jean Ritchie, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Josh White, Odetta—and later the two young folk singers Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Bearden enjoyed playing guitar and singing at house parties and other communal gatherings. He would perform such songs as “Man of Constant Sorrow”; “Big Ball in Boston”; “Baby Please Don’t Go”; “See that My Grave is Kept Clean”; “Hit the Road Jack”; “Outskirts of Town”; “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out.” He especially loved the blues and spent hours listening to recordings of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Furry Lewis, Robert Johnson, and Big Bill Broonzy while attempting to learn their chords and guitar licks.

When called upon he could also produce credible renditions of Mexican rancheras. Ron Padgett remembers that Bearden would play such songs as Ella, El Jinete, Escaleras de la Carcel, La Cama de Piedra by the Mexican musician Miguel Aceves Mejia and sing them with great feeling.

During Bearden’s fourth college year, he withdrew from TU after being suspended for poor scholarship. Bearden and Judith, now married, put Tulsa in their rear-view mirror for good. In the Fall of 1962, they drove to New York City to join Berrigan, Padgett, Brainard, and Gallup, who were living there and sending back favorable reports. Thus, the core elements of the so-called Tulsa School of Poets were no longer living in Tulsa.

New York City (1962-1964)

Shortly after David and Judith Bearden arrived in the Big City, their car was broken into and all of their belongings were stolen, including a suitcase full of his manuscripts. Undaunted, they rented an apartment on East 7th Street on the Lower East Side, but he grew to dislike Manhattan intensely, calling it a place full of “men dressed up in monkey suits, working in cages.” Nor did he find the collegial New York art and poetry scene, with its round of cocktail parties and gallery openings, suited to his outspoken personality and competitive nature. It was a scene that has been described by Daniel Kane, in his book, All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s, as prizing “informality, chattiness, a sense of casual erudition…” while David Bearden had always cultivated the self-image of the poet as a brooding and solitary outsider. Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Ezra Pound, even Bob Dylan in his alienated protest-singer mode, were closer to his ideals. In this, he differed in style and attitude from the gregarious Berrigan and the more low-key Padgett and Gallup. The three of them along with Joe Brainard, who was making a name for himself in the art world, embraced New York while moving rapidly away from their Oklahoma beatnik beginnings.

One occasion in New York was when Bearden and the other Tulsans found themselves publishing their work together. It was in an ephemeral mimeograph publication called The Censored Review, edited by Ron Padgett. It came about after the administrators at Columbia University objected to Ron’s intention to include poems by Ted Berrigan and David Bearden in an issue of The Columbia Review, the university’s official literary magazine. Ted’s poem was deemed obscene for using the word “fuck,” and David's was considered to be unacceptably scatological for containing the words “shit” and “turd.”

Because of the ban, a furor erupted that was covered by the local press, and Padgett was even interviewed on TV. The student editors of The Columbia Review resigned in protest and The Censored Review was printed by an off-campus social organization. Priced at 25 cents, it sold out all 800 copies immediately and was a prototype for the type of inexpensively produced chapbooks and magazines that would flourish in the 1960s and ‘70s as the “Mimeo Revolution.”

In a review appearing in the Columbia Daily Spectator, Angus S. Fletcher, an assistant professor of English wrote, “The most accomplished poem here is the one that caused the most furor … Bearden’s ‘The Desk is a Frozen Sea.’ The verse is refined and ingenious, full of carefully controlled off-rhymes and assonantal effects. Its strict stanzaic form gives order to the whole. One simply accepts the idea of the poem, that the creative process, in this cosmic instance, is a painful, narcissistic exertion...”

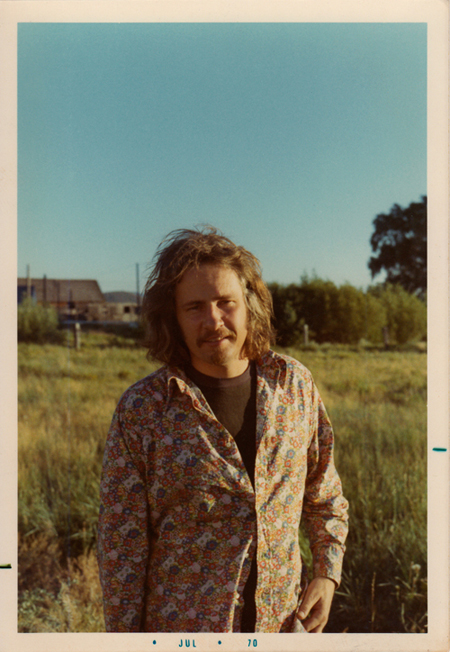

California (1964-1975)

In 1964, Bearden and his family moved to San Francisco after their time in New York City. They first lived on Baker Street in a quiet working-class Russian neighborhood that was evolving into what would become the famed Haight-Ashbury district. Shortly thereafter they moved further east into a house on Fell Street.

He soon became associated with Charles Plymell, the Kansas Beat poet and publisher and his posse of Midwestern writers and artists known as the “Wichita Vortex.” Plymell, who had his own offset printing press, produced a number of underground, avant-garde publications, including three issues of a magazine called Bulletin from Nothing. In its first issue, a poem titled “In a Cantina” by David Omer Bearden appeared along with works by such Beat luminaries as William Burroughs, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Antonin Artaud, Ed Sanders, and Bob Kaufman. He later got to know Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, and Neal Cassady whom he hero-worshipped at the time. Cassady—ever the hustler and the con man and always with an eye on the main chance, returned the favor, by frequenting David and Judith’s Fell Street apartment where he held forth in his typically garrulous and rambunctious way, while being simultaneously egged-on and counterpointed by Bearden.

Other members of his San Francisco circle included artists and poets such as, Steven Lieper, Dion Wright, Daniel Abdal-Hayy Moore, Maureen Owen, Roxie Powell, Bob Branaman, and Alan Russo who called him “our Blythe spirit." *

During this period Bearden published poems in a number of West Coast, small-press magazines. He also edited and published a chapbook called LeFeuDuCiel, an anthology containing his own works and those by several former Tulsans, members of the Wichita Vortex, Ezra Pound, and Gerard Malanga, who he had met in New York. It was the first of a number of chapbooks he would produce under the imprint of Rosace Publications.

After two years living on Fell Street, by 1966 they left San Francisco to move to Vinton, Plumas County, CA, in the Sierras. Judith Bearden got a job teaching at an elementary school in a nearby town called, Loyalton and David worked as a lumberjack and operated a combine. David and Judith Bearden lived in Vinton for five years and then moved to Vacaville, CA.

* To learn more about the San Francisco period, please see commentaries, Drugglers by Dion Wright and Bruce Conner by Daniel Abdal-Hayy Moore.

Music with Judee Sill (1972-1975)

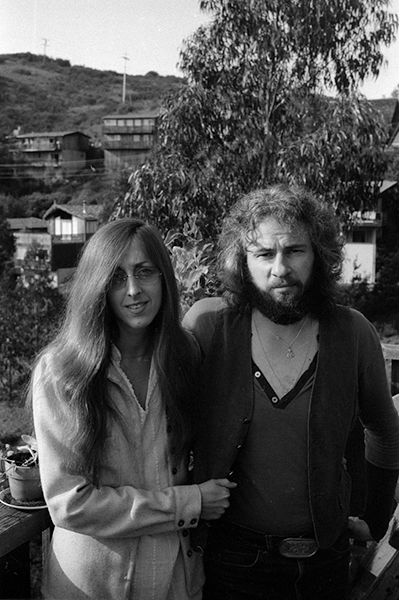

In the early 1970s, while still married, Bearden became romantically and artistically involved with the tragic singer/songwriter Judee Sill. Sill was the first artist signed to David Geffen's Asylum Records label and released two critically acclaimed albums but not commercially successful. Her music style is regarded as mystic Christian folk with influences by classical composers such as Mahler, Beethoven, and especially Bach.

Bearden had heard Sill perform on television in San Francisco, and a mutual friend named Steve Leiper introduced them in Mill Valley. They got together and recorded her second album, Heart Food in Los Angeles, in 1973, which was dedicated “With Love to David Omer Bearden.” He wrote the lyrics to one of the cuts on the album—the solo piano song titled “When the Bridegroom Comes.”

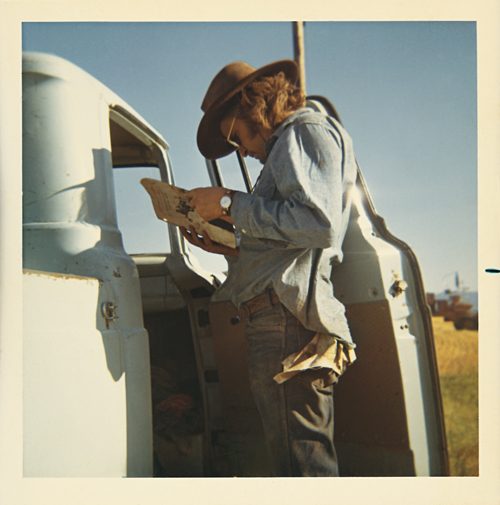

They toured England with Roy Harper and Jimmy Page and performed at the legendary Royal Albert Hall, among other venues. David Bearden fulfilled the role of a Cowboy-Jesus figure for Judee Sill, accompanying her on the guitar. She gave him solo time onstage covering Hank Williams’ songs like “Someday You'll Call My Name” and “Weary Blues." While on tour, they kept an intimate joint diary released in Bearden’s 2018 poetry book, The Mental Traveler.

They engaged in an affair that they saw as a spiritual quest, despite being one that involved them abusing drugs together. They thought of themselves as genderless angels with a message for the world and a cross to bear. Although their relationship had a lightning bolt effect of extreme intensity for each of them, it was also a rough crossing. Neither could establish domestic happiness and would be unfaithful to the other whenever they got bored. Eventually, their relationship failed. Sill’s use of substances was more severe and ongoing and eventually claimed her life in 1979. Bearden’s and Sill’s karmic destiny compelled them to the wild dance of love and creating music together while not releasing either of them from their demons. All this effectively put an end to his marriage with Judith Bearden, and in later years, he confessed that the affair's impact on his wife was his greatest regret.

In response to Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill documentary.

For more pictures and information, please see music.

Later Years (1985-2008)

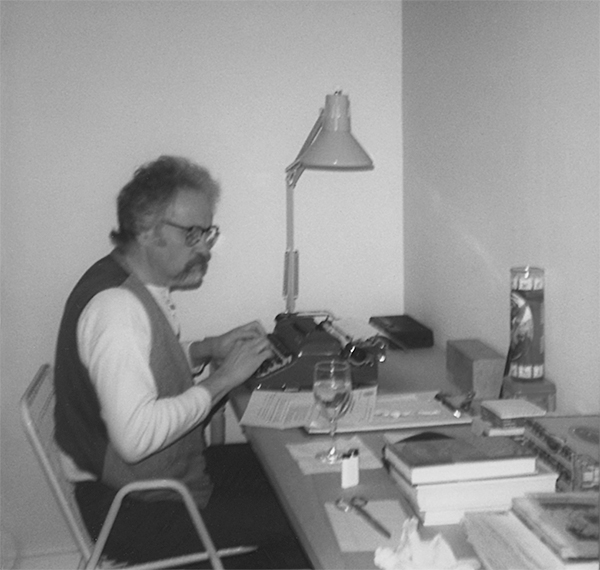

In 1985, Bearden relocated from Seattle to Hopatcong, NJ, and moved in with an old college friend from Tulsa. He started working on a manuscript called The Mental Traveler, which included many of his earlier writings and new ones, but unfortunately, it remained unpublished for nearly thirty years.

While living in New Jersey, Bearden met his “Muse,” Johanna Beck, and her two daughters. Johanna worked as an executive secretary and personal assistant at the Albert B. Grossman Management firm in New York City from 1965 to 1969. Grossman was the manager of several well-known recording artists, including Peter Paul and Mary, Bob Dylan, Richie Havens, Odetta, Gordon Lightfoot, Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and many others. Bearden and Johanna later moved to Moscow, PA, while embracing the mission to raise her two daughters. Eventually, his drinking ended their romantic relationship, but they remained involved in each other's lives. Later, he would move to Scranton, PA, where he spent his final fifteen years.

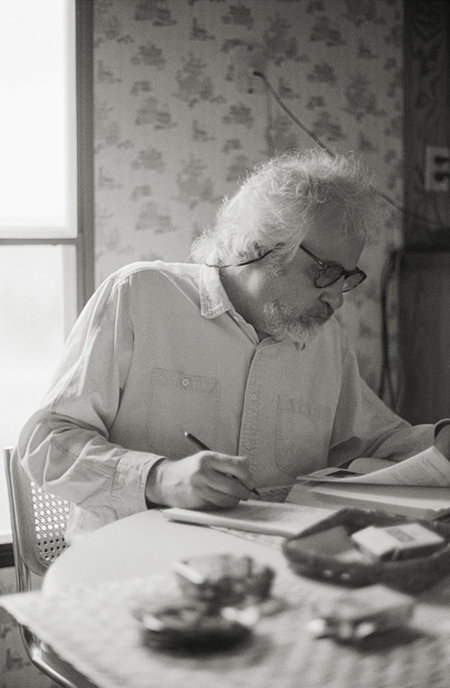

He continued to write during this period and worked at various jobs before becoming the night manager and caretaker for the residents of St. Anthony’s Haven Shelter. While off duty, he embraced service work by carrying sandwiches to give out to the homeless when he walked around town. He also wrote “The Homeless Stars,” a poem influenced by his experiences at the shelter, which appeared in a staff publication called Welcoming Hands Newsletter.

When not working at the shelter Bearden devoted much of his time to schmoozing and observing the scene in a local bar called Pat Langan’s, which inspired his final work—a neo-surrealistic, Joycean piece of prose-poetry called: The Thing in Packy Innard’s Place. The book can be read as a work of high fantasy coupled with an affinity for the quotidian that evokes his life in Scranton, its people, architecture, and its natural setting.

Death

Towards the end of Bearden's life, he suffered from the effects of hepatitis C which he had contracted while working at the homeless shelter. He had been accidentally punctured by a syringe left on a sofa by one of the residents. Though he realized his condition would sooner or later be fatal, he opted not to consider drastic medical interventions.

David Bearden passed away on September 4, 2008, in Scranton, PA, at 68.